Positive Health Online

Your Country

The Glutes and the Gait Cycle - Extract from The Vital Glutes

listed in anatomy and physiology, originally published in issue 229 - April 2016

This is an extract from The Vital Glutes by John Gibbons. Lotus Publishing. 2014.

Chapter 3: The Glutes and the Gait Cycle

We take walking for granted - it is something that we just do without understanding what exactly is going on - until we suffer pain somewhere in our body, and then the simple action of walking becomes very painful. What I would like to do in this chapter is to discuss in detail what exactly happens when we walk (you might want to go through the movements yourself as they are described).

Gait Cycle

Definition: A gait cycle is a sequence of events in walking or running, beginning when one foot contacts the ground and ending when the same foot contacts the ground again.

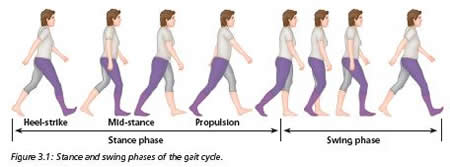

The gait cycle is divided into two main phases: the stance phase and the swing phase. Each cycle begins at initial contact (also known as heel-strike) of the leading leg with a stance phase, proceeds through a swing phase, and ends with the next contact of the ground with that same leg. The stance phase is subdivided into heel-strike, mid-stance, and propulsion phases.

Human gait is a very complicated, coordinated series of movements. Another way of thinking about the gait cycle is that the stance phase is the weight-bearing component of each gait cycle. It is initiated by heel-strike and ends with toe-off from the same foot. The swing phase is initiated with toe-off and ends with heel-strike. It has been estimated that the stance phase accounts for approximately 60% of a single gait cycle, and the swing phase for approximately 40%.

Figure 3.1: Stance and swing phases of the gait cycle.

Heel-Strike

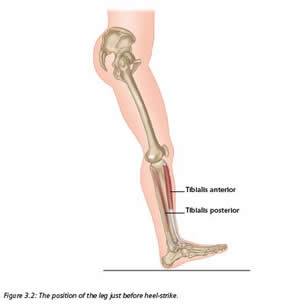

If you think about the position of your body just before you contact the ground with your right leg during the contact phase of the stance phase, the right hip is in a position of flexion, the knee is extended, the ankle is dorsiflexed, and the foot is in a position of supination. The tibialis anterior muscle, with the help of the tibialis posterior, works to maintain the ankle/foot in the position of dorsiflexion and inversion (inversion is part of the motion referred to as supination).

Figure 3.2: The position of the leg just before heel-strike.

In normal gait the foot strikes the ground at the beginning of the heel-strike in a supinated position of approximately 2 degrees. A normal foot will then move through 5-6 degrees of pronation at the subtalar joint (STJ) to a position of approximately 3-4 degrees of pronation, as this will allow the foot to function as a ‘mobile adaptor’.

A Myofascial Link

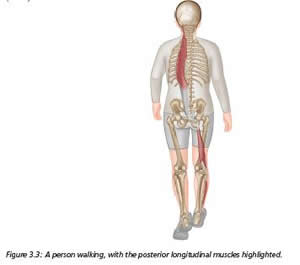

As a result of the foot being dorsiflexed and supinated, the tibialis anterior (which is the main muscle responsible for this anatomical position and has an insertion on the medial cuneiform and 1st metatarsal) is now part of a link system that we will call a myofascial sling. This sling, starting from the initial origin of the tibialis anterior, continues as the insertion of the peroneus longus (onto the 1st metatarsal and medial cuneiform, as in the case of the tibialis anterior) to its muscular origin on the lateral side and head of the fibula. This bony landmark is also where the biceps femoris muscle inserts. The sling now continues as the biceps femoris muscle toward its origin on the ischial tuberosity, where the muscle attaches to the tuberosity via the sacrotuberous ligament; often the biceps femoris directly attaches to this ligament rather than to the ischial tuberosity, and some authors have mentioned that potentially 30% of the biceps femoris attaches directly to the inferior lateral angle (ILA) of the sacrum. The sling then carries on as the sacrotuberous ligament, which attaches to the inferior aspect of the sacrum at the ILA and fascially connects to the contralateral multifidi and to the erector spinae that continue to the base of the occipital bone. This myofascial sling is known as the posterior longitudinal sling (PLS).

Figure 3.3: A person walking, with the posterior longitudinal muscles highlighted.

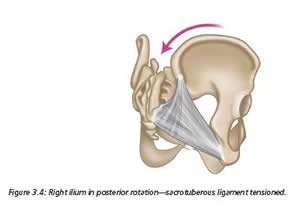

So even before you contact the ground, the posterior longitudinal sling is being fascially tensioned; the increased tension is focused on the sacrotuberous ligament via the attachment of the biceps femoris. This connection will assist the force closure mechanism process of the SIJ; in simple terms, this creates a stable pelvis for the initiation of the weight-bearing gait cycle. You may also notice that the right ilium (see Figure 3.4) undergoes posterior rotation during the swing phase and this will assist the closure of the SIJ because of the increased tension of the sacrotuberous ligament.

Figure 3.4: Right ilium in posterior rotation - sacrotuberous ligament tensioned.

You might want to stand and slowly go through the following movements so that you can get a sense of what happens with your body in normal walking. As explained above, just before the heel-strike phase your hip will be flexed, your knee extended, and your ankle dorsiflexed with the foot supinated. The tibialis anterior and tibialis posterior maintain this position of the ankle and foot, and as you contact the ground, these two muscles are responsible for controlling the rate of pronation through the STJ by contracting eccentrically.

As your right leg moves from heel-strike to toe-off, your body weight begins to move over your right leg, causing your pelvis to shift laterally to the right. As the movement continues toward toe-off, your right pelvic innominate bone begins to rotate anteriorly while your left innominate bone begins to rotate posteriorly.

As you continue with the gait cycle, you now enter the mid-stance phase of gait and this is where the hamstrings should reduce their tension by the natural anterior rotation of the pelvis and the slackening of the sacrotuberous ligament. This is the point during the mid-stance phase where the Gmax should take the role of extension.

Phasic contraction of the Gmax occurs in the mid-stance phase: the Gmax simultaneously contracts with the contralateral latissimus dorsi - it is this muscle that will extend the arm through what is known as counterrotation, to assist in propulsion. The thoracolumbar fascia, which is a sheet of connective tissue, is located between the Gmax and the contralateral latissimus dorsi, and this fascial structure is forced to increase its tension because of the contractions of the Gmax and latissimus dorsi. This increased tension will assist in stabilizing the SIJ of the stance leg through force closure.

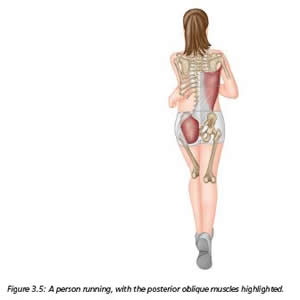

If you look at Figure 3.5, you can see that just before heel-strike, the Gmax will reach maximum stretch as the latissimus dorsi is being stretched by the forward swing of the opposite arm. Heel-strike signifies a transition to the propulsive phase of gait, at which time the Gmax contraction is superimposed on that of the hamstrings. Activation of the Gmax occurs in conjunction with contraction of the contralateral latissimus dorsi, which is now extending the arm in unison with the propelling leg. The synergistic contraction of the Gmax and latissimus dorsi creates tension in the thoracolumbar fascia, which will be released in a surge of energy that will assist the muscles of locomotion, reducing the overall energy expenditure of the gait cycle. Janda (1992, 1996) mentions that poor Gmax strength and activation is postulated to decrease the efficiency of gait.

Figure 3.5: A person running, with the posterior oblique muscles highlighted.

As we progress from the mid-stance phase to heel-lift and propulsion, the foot begins to re-supinate and passes through a neutral position when the propulsive phase begins; the foot continues in supination through toe-off. As a result of the foot supinating during the mid-stance propulsive period, the foot is converted from a ‘mobile adaptor’ (which is what it is during the contact period) to a ‘rigid lever’ as the mid-tarsal joint locks into a supinated position. With the foot functioning as a rigid lever (as a result of the locked mid-tarsal joint) during the time immediately preceding toe-off, the weight of the body is propelled more efficiently.

Pelvis Motion

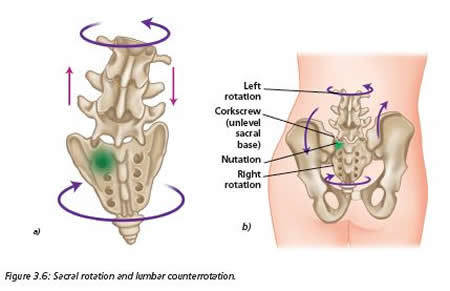

Next we will take a look at the pelvis and how it functions during the mid-stance phase. As the right innominate bone starts to rotate anteriorly from an initial posterior rotated position, the sacrum will be forced to move into what is called a right torsion on the right oblique axis. In other words, the sacrum rotates to the right, and side bends to the left, because the left sacral base moves into an anterior nutation position (this is also known as Type I spinal mechanics, as the rotation and side-bending are coupled to opposite sides). Owing to the kinematics of the sacrum, the lumbar spine rotates left and side bends to the right, the thoracic spine rotates right and side bends to the left, and the cervical spine rotates right and side bends to the right. The cervical spine coupling is opposite to that of the other vertebrae since its spinal mechanics are Type II (Type II means that rotation and side-bending are coupled to the same side). As the left leg moves from weight bearing to toe-off, the left innominate, the sacrum, and the lumbar and thoracic vertebrae undergo torsion, rotation, and side-bending in a similar manner to that described above, but with movements in the opposite directions.

Figure 3.6: Sacral rotation and lumbar counterrotation.

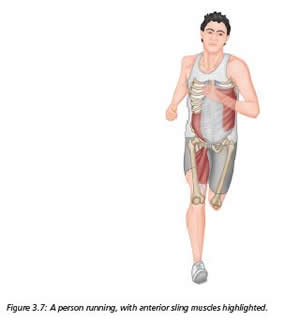

The anterior oblique also works in conjunction with the stance leg adductors, ipsilateral internal oblique, and contralateral external oblique muscles, as shown in Figure 3.7. These integrated muscle contractions help stabilize the body on top of the stance leg and assist in rotating the pelvis forward for optimum propulsion in preparation for the ensuing heel-strike.

Figure 3.7: A person running, with anterior sling muscles highlighted.

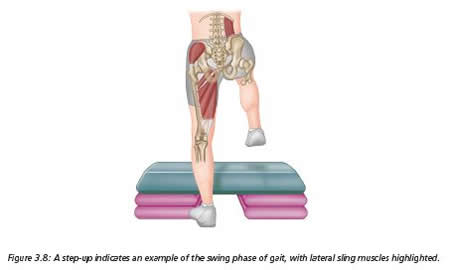

The swing phase of gait utilizes the lateral system, as we have entered the single-leg stance position. This sling connects the gluteus medius (Gmed) and gluteus minimus (Gmin) of the stance leg, and the ipsilateral adductors, with the contralateral quadratus lumborum (QL). Contraction of the left Gmed and adductors stabilizes the pelvis, and activation of the contralateral QL will assist in elevation of the pelvis; this will allow enough lift of the pelvis to permit the leg to go through the swing phase of gait. The lateral sling plays a critical role, as it assists in stabilizing the spine and hip joints in the frontal plane and is a necessary contributor to the overall stability of the pelvis and trunk.

Figure 3.8: Swing phase of gait, with lateral sling muscles highlighted.

Maitland (2001) mentions that proper body movement while walking is influenced by the ability of the sacrum to cope with left torsion on the left axis and right torsion on the right axis. Since most walking is accomplished with your vertebral column relatively upright and vertical, for the purpose of this discussion we will assume that your spine and sacrum are in neutral while you walk.

The way our axial skeletal system alternately undulates in side-bending and rotation as we walk is very interesting and extremely important to our overall well-being. It is a movement that is reminiscent of the undulating action of a snake as it slithers through the grass. The big difference between a snake and a human, of course, is that our snakelike spine has ended up being given two legs on which to walk.

Further Information

Available from Amazon

www.amazon.co.uk/The-Vital-Glutes-Connecting-Dysfunction/dp/1583948473

www.amazon.com/The-Vital-Glutes-Connecting-Dysfunction/dp/1583948473

Comments:

-

No Article Comments available