Positive Health Online

Your Country

Treating the Complex Shoulder

by Simeon Niel-Asher(more info)

listed in bodywork, originally published in issue 130 - December 2006

Shoulder problems are common; as many as one in four adults suffer shoulder problems at some time; rotator cuff tendinopathy, capsulitis, arthritis of the glenohumeral joint, impingement syndrome, post operative/fracture stiffness, etc. Yet to-date, there has been no comprehensive, reproducibly successful, and evidence- based treatment. Often physical therapists employ a range of approaches and modalities on a hit or miss basis, a type of ‘suck-it and see’ approach.

The shoulder joint is not one, but a series of four inter-related joints; it is a complex arrangement, and much can go wrong with it. It comprises the glenohumeral (ball and socket joint), the muscular scapulothoracic joint, the acromiclavicular and the sterno-clavicular joints. These four joints function in different ways to stabilize the shoulder for fine hand and wrist motion, and to provide a stable framework for the massive and unique permitted range of shoulder motion. Circumduction of the glenohumeral joint is the largest range of motion for any joint in the body. To accomplish this mobility, our upper limbs have been massively modified when compared, for example to our hip joints. This mobility comes at a price; in the case of the glenohumeral joint this means poor stability. Dislocations are common; these can be forward (anterior), backwards (posterior) or upwards (luxator).

To stabilize these joints there is a further complex arrangement of ligaments and muscles. Most pertinent to this article are the glenohumeral joint, the rotator cuff and the biceps muscles. I will discuss these three in further detail.

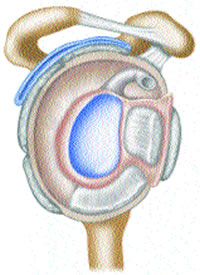

The Glenohumeral Joint ©SNA 2006

The Glenohumeral Joint

The glenohumeral joint is covered by a capsule; this is reinforced by thickenings anteriorly, posteriorly and laterally, and collectively called the glenohumeral ligaments. The capsule of the joint is massive and dependant; this means that it hangs downwards, folding inferiorly into a type of pouch. When the upper extremity is fully raised (180°) the capsule is held tight, but once by the side of the body, this capsule forms a loose pouch. The capsule of the glenohumeral joint contains between 70 to 90ml of synovial fluid; this fluid is generated and replenished by unimpeded articulation of the cartilaginous surfaces which literally squeeze synovial fluid into the capsular space. Above the Glenohumeral joint is the subacromial (subdeltoid) bursa.

When irritated, as in a frozen shoulder (capsulitis), the capsule becomes highly vascularized and inflamed. If this situation becomes chronic, this capsular synovitis causes it to ‘shrink-wrap’ around the joint and may lead to adhesions. It is not uncommon for there to be a mere 5ml of synovial fluid in a severely irritated frozen shoulder, partly related to the lack of motion. Furthermore, capsular synovitis may lead to subacromial bursitis.

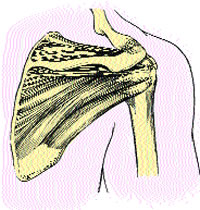

Rotator Cuff

Rotator Cuff

The rotator cuff consists of four muscles, three of which – Subscapularis, Infraspinatus and Teres Minor – blend together to form a single (conjoined) tendon – the Rotator Cuff Tendon (RCT). The Supraspinatus tendon, blends with this conjoined tendon, but inserts slightly anteriorly.

The cuff muscles stabilize the glenohumeral joint, bringing it backwards and downwards. This affords maximum stability for the shoulder girdle, thus allowing us to perform tasks with the hand, wrist and elbow joints, whilst the shoulder joint is at various angles.

Movements of the cuff muscles are carefully coordinated by the brain, and damage to one of these four muscles will lead to a compensation and deficiency in the others. Unfortunately, poor posture, over-use, and many other factors, often lead to damage in one or more of these muscles.

The rotator cuff is vulnerable to a number of conditions:

• Peri-arthritis – this is soft tissue arthritis and is now considered to be a major factor in shoulder problems;

• Impingement – by a bony spur, an anomalous clavicle or bursitis;

• Tears – both inter and intra substance;

• Rupture – full or partial thickness;

• Calcification;

• Tendinopathy.

Understanding the way the cuff muscles coordinate gives us a tremendous amount of insight into shoulder function; we will discuss this later.

The Biceps Muscle

The Long Head of the Biceps (LHB) tendon has a unique relationship with the capsule. The tendon originates just above the socket of the glenohumeral joint. It runs laterally across the top of the humerus within its sheath until it becomes deviated inferiorly through the bicipital groove of the humerus. After running down the humerus for approximately five to six centimeters, it blends with the biceps muscle to form a musculo-tendinous junction. From there, it blends with fibres from the Short Head of the Biceps (SHB) to form the main belly of the biceps.

It can be argued that a primary inflammation and Stenosis in the region of the LHB tendon could spread to involve the capsule itself. This has been borne out through the careful clinical observation of several hundred cases. Because the LHB is intracapsular, inflammatory cells, exudates and products of the inflammatory cascade can track along the tendon directly into the capsule. Once inside the capsule, the inflammation and synovitis seems to spread rapidly.

The Niel-Asher Technique®™

Over the years, I have come to realize that far from being complicated, the shoulder has a sublime simplicity to it.

Reducing the shoulder to its component parts is useful for understanding the structures, but does not really give us a true understanding of the shoulder. Movement is how we communicate with the outside world; how we express who we are. The musculoskeletal system performs this function.

Sensory feedback from receptors embedded in the musculoskeletal system creates a complex cascade of input into the somatosensory cortex. This can be visualized as an orchestral symphony. In shoulder problems this symphony is playing out of tune.

The sensory and motor cortex lies near the median fissure of the large cerebral hemispheres. This is where modulation of sensation (somatosensory) and control of movement (somatotrophic) occurs; where the conductor stands. Further examination of this region will help us unlock some secrets of the shoulder.

Homunculus

The motor homunculus is the four limbed blueprint of the body ‘hard-wired’ into our motor cortex. This map is distorted according to the complexity of movement, the enlarged areas designating those with the highest level of motor innervation.

Voluntary movement in the body is initiated at the level of the motor cortex. Muscle tone, stretch and velocity are monitored by proprioceptors and stretch receptors, and relayed back to the sensory cortex, and adjustments made accordingly.

It has been suggested that, far from being hard wired, our motor homunculus relies on the feedback from the sensory homunculus to reinforce and maintain this innate self-image.

Conditions such as phantom limb pain may result from a mis-communication or ‘de-afferentiation’ between the afferent sensory and efferent motor homunculi. It has been suggested (Ramachandran and Blakeslee 1998) that the lack of sensory referencing may be a significant factor in phantom limb pain.

Patterns of Movement

All patterns of movement involve multiple fixators, agonists and antagonists. Normally, these movement patterns are superimposed and orchestrated effortlessly by the motor cortex to create movement. However, dysfunction in one or more muscles disrupts this innate balance, forcing the body to adopt compensatory patterns of movement.

In conditions such as frozen shoulder syndrome and rotator cuff tendinopathy the brain is forced to functionally reorganize all movement patterns, due to the contracture of intra- and extra-articular structures. It is then forced to recruit different muscles as agonists and antagonists.

The body will strive to maintain maximal movement for as long as possible, but eventually as the relationships of coordination deteriorate, movement becomes rapidly limited. Furthermore, I have observed that some sort of neurological switching takes place where the agonist/antagonists relationship gets switched around. The Biceps seems to pair off with the Teres minor muscle and the Triceps with the Pectoralis minor.

The way the motor cortex changes its coordination pattern in many shoulder syndrome seems to be the same for everyone. By observing the way in which it adapts I have developed the key to ‘demystifying’ the complex shoulder. And, by manipulating a choreographed series of coordinated trigger points and other reflex neurological inputs, I have been able to find a way to fool the brain into switching the confused neurological and muscular relationships back to normal.

Cortical-Neuro-Somatic-Programming®™ (CNSP)

This is the term I have coined as it seems to best describe my theory. Some of you may well be familiar with Neuro-Linguistic-Programming (NLP). This system recognizes that we filter the world around us through the following sensory inputs or ‘submodalities’ and internal feelings). Most of this occurs at the unconscious level. NLP recognizes that we create real and powerful ‘internal’ neuropsychological patterns based on the way we filter, file and respond to these sensory experiences of ‘your perceptions determine your reality’. NLP offers a system to re-programme the mind and change the pre-conceptions which may be holding us in negative patterns. It does this by manipulating the sensory submodality inputs in specific and repeatable ways.

The primary NLP tool for affecting a neuro-dynamic change is through language hence, ‘linguistic’. It is interesting to note here that once you understand that we create our internal world, and this realization allows us to be ‘prescient’, we can change our world!

The Niel-Asher Technique®™ utilizes a similar model. The primary CNSP tool for affecting a neuro-dynamic change is through stimulating a specific sequence of reflexes at the level of the somatosensory cortex and the spinal cord, hence ‘somatic’.

Treatment

The treatment I have developed is hands-on. It involves using a unique and reproducible sequence of trigger points, neural reflexes and stretching manoeuvres. Some of it can be painful whilst other parts are soothing. This is for a reason. As you are well aware, the tissues of the body are perfused with receptors; some respond to deep touch others to superficial; some to pain, some to pressure, others to vibration, hot or cold. The whole of a human’s experience to its environment is mediated through our tissues’ sensory receptors. Our tissues sense the world around us and translate these sensations into messages that our brain decodes stimuli.

My technique differs from other physical therapy techniques, not so much by what is done, but by the sequence in which it is performed. It is the sequence that stimulates the damaged tissues to fire off attenuated efferent proprioceptive signals to the brain. These signals are in specific patterns.

Evidence-Based Technique

The Niel-Asher Technique®™ is evidence-based. In a Randomized Placebo Controlled Trial, conducted in association with the Rheumatology Research Unit at Addenbrookes hospital (Cambridge, UK), the technique was compared to a standard physiotherapy protocol (with exercise) and placebo for the treatment of frozen shoulder syndrome (British Journal of Rheumatology. 42 (Suppl 1). Article 418 BHPR p.146. 2003).

Results

• Significantly increased range of motion Increased ROM active abduction over and above physiotherapy (TNAT 52.6° (p=0.0002), 24° physiotherapy and 0.8° placebo) (p=0.002);

• Eighty percent reduction in pain The largest clinical change in reducing shoulder pain and disability (an 80% decrease) as measured on the shoulder pain and disability index (SPADI). TNAT 38.7 points physiotherapy 19.9 placebo 22.8. (p=0.07);.

• Significantly increased strength and power A significant increase in strength and power; the physiotherapy group stayed the same and the placebo group decreased (as measured by a cybex dynamometer) – even though no exercises were given (p=0.043).

Further Information

Defrost Training: A four module, eight-day distance learning course ‘Treating the complex shoulder’ is available now. The course is certificated, and qualified practitioners are listed on the number one Google listed website www.frozenshoulder.com The course is open to all hands-on therapists worldwide. For more information visit www.defrosttraining.com or the courses section at the back of this magazine.

Comments:

-

joseph cope said..

the same technique/technical theory...? can it be applied to anywhere on the body?... considering the practitioner knows the "sensory cascade" of that particular muscle group?

any more information would be appreciated.

Thankyou

Regards:

Joseph Cope