Positive Health Online

Your Country

Gut Health, the Immune System and Mental Health

by Catherine Rogers(more info)

listed in colon health, originally published in issue 257 - September 2019

The Microbiome - What it is and Why it is Important

The human microbiome is the microorganisms that live on our skin, inside our gut and other body cavities like our nostrils. For instance, bacteria outnumber the number of human cells in our bodies ten-fold according to the Human Microbiome Project (https://hmpdacc.org/ihmp/overview/).

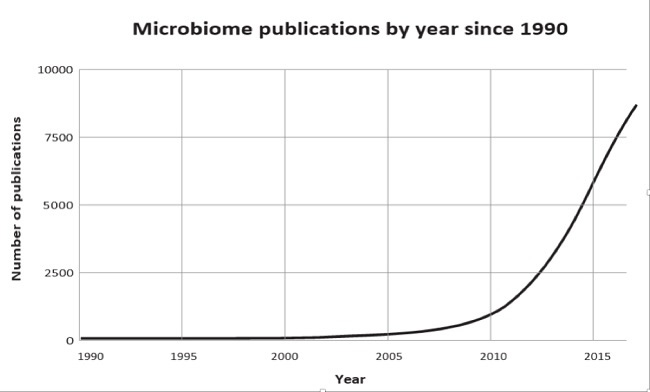

Encouragingly, there is an ongoing paradigm shift especially within lifestyle and functional medicine, for medical practitioners to view the human body as an ecosystem made up of many different organisms, like a rainforest or coral reef. The recent discovery of the immense impact of these microbes on our bodily performs is beginning to transform medical practice and academic research is available to support this shift; the graph below shows how much research has been done on the microbiome (gut bacteria) since 2015!

The trillions of microbes have multiple essential functions in the body: some produce important signaling molecules;[1] others help immune cells develop;[2] and bacteria in the gut help to digest food, providing up to 15% of your required calories by breaking down food that we ourselves cannot process.

Within the gut, so called ‘good’ bacteria crowd out microbes that cause infection and create essential metabolic products; they produce B vitamins which send signals via other molecules in a complex process to produce short chain fatty acids that reduce inflammation and help the gut lining to stay intact. ‘Good’ bacteria also activate the production of neurotransmitters that determine multiple things including our mood. So, our microbiome is key to good physical and mental health!

However, our modern lifestyle and Western diet is disrupting this balance within our microbiome. We are eating less and less fibre which is the fuel for our gut bacteria.[3]. This leads to the loss of bacteria which have controlled the expression of our genetic code for centuries via the process of switching genes on or off (called epigenetics). Scientists have even begun to set up a ‘bacteria bank’ to preserve our microbial strains before extinction so that we can repopulate our guts with good bacteria in the future!

What we consume has a profound impact on our gut health so it is important to provide our gut with the best nutrition we can. I have made this possible via the www.resetyourguthealth.com programme which based on the science of gut health as outlined in my fully referenced book Gut Well Soon The programme removes inflammatory foods, adds in enzyme rich food for better digestion and food that helps heal the gut.

It will provide meal plans personalised to specific health challenges, such as type II diabetes, arthritis, migraines and more and also caters for individual food preferences and allergies. It even automatically generates shopping lists for your chosen period. It is so much more than a cookery book and is an amazing tool being used by both health professionals and individuals. I would encourage anyone to try the 3-day free trial, read the blogs, search the 180 + FAQs and downline the free guidelines. It really is an incredible resource and very good value, £48 for lifetime access!

I am passionate about reducing the burden of chronic disease on friends, family and the NHS bill. According to over 400 nutritional experts across the globe meeting at the True Health Initiative in the US[4] the best diet to achieve this is a Mediterranean-style diet and www.resetyourguthealth.com enables users to make this sort of eating a daily habit. Enough of the programme and back to the science!

Physical Health

The gut is key to physical health, especially in regard to the immune system. It is estimated that 70% of the body’s immune system is located in the gut due to the proliferation of gut-associated lymphoid tissue [5] which is supported by the microbiome. Deficits in the gut microbiome can therefore significantly affect our physical health. For instance, people who suffer from asthma and allergies[6] and obesity[7] are more likely to have less diversity in their gut bacteria and may find themselves to be more lethargic and generally lacking energy.[8] This may be due to a diet of excessive sugar and saturated fat altering the balance between bacteria species, such as Bacteriodes and Firmicutes. Bacteriodes are used to digest fibre whilst the Firmicutes digest fat. A poor diet can encourage the growth of the population of Firmicutes bacteria, thus dictating if your body is lean or obese.

Research in mice models, including mice that are raised in artificially germ-free environments which prevent the development of immune-related microbiota, has shown that microbes associated with obesity can affect insulin resistance, fat deposition, metabolism, appetite and inflammation.[9] Though this is limited to mice for now, it is likely that further research will establish similar links in humans.

Raw Cauliflower Shawarma: Image Courtesy of the Author

Top Tips: Diet and the Microbiome

Avoid processed and sugary foods

Many studies have shown that processed and sugar-laden foods are associated with various negative effects on our physical health both directly and indirectly via other conditions especially obesity. For example, people with sugary diets are 54% more likely to be obese than those that consume very little sugar[10] and obesity is linked as a risk factor to multiple different cancers[11, 12, 13]. One study found that when a rural African population with a basal low level of cancer were given an average Western diet of processed food, sugar etc., the number of inflammatory markers associated with cancer increased.[14] Similarly, when an African American population switched to a traditional African diet of beans, peas, lentils etc. showed a decrease in the same markers after just 2 weeks.[14] This Western diet can alter the composition of the gut microbiome, for instance participants who ate only McDonald’s for 10 days lost 1400 bacterial species from their gut - a third of their microbiome.[15] And this disruption can cause chronic diseases.

Sugary drinks are particularly influential on our health for multiple reasons. Not only are they associated with the increase in tooth extractions due to cavities every year[16] but just 100g of sugar in a fizzy drink lead to 40% decrease in effectiveness of white blood cells in children.[10] Over the long term, drinking sugary drinks are associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease[17], heart disease, type 2 diabetes and pancreatic cancer[18, 19].

For a healthy gut and healthy body, it is therefore best to avoid processed food and sugar!

Aim for Fruit and Vegetables

Fruit and vegetables are key to a healthy balanced diet rich in vitamins and fibre which fuels the bacteria in our gut and helps to maintain a healthy digestive system and bowel movements[20, 21]. Polyphenols are also present in fruit and veg which are phytochemicals that reduce oxidative stress by regulating the production of free radicals, which can lead to bodily inflammation.

A good example of a vegetable that is good for your health is broccoli. Broccoli is high in vitamin C which protects the body against viruses and infections by bolstering the immune system.[22] It is also high in vitamin K which strengthens bones, therefore potentially protecting against osteoporosis and weakened bones with age.[23] It also contains a compound called sulforaphane which has been suggested to help prevent colon cancer.[24, 25]

Top Tip: Sleep and the Microbiome

Improve your sleep, improve your gut, improve your health

It may seem with our busy modern lives that sleep is difficult to come by, but it is incredibly important to maintain and promote our physical health. After a short period of reduced sleep, the body is more vulnerable to infection, prone to fatigue and lack of motivation.[26, 27] In the long term, chronic sleep deprivation or poor sleep affects cognitive function and increases the risk of diabetes, heart disease, obesity and stroke.[27, 28] On the molecular level, people who regularly get less than 6 hours sleep had elevated levels of proteins associated with inflammation compared to people getting 7-8 hours’ sleep a night.[29]

It is also the timing of sleep which is important to quality. The WHO reports that regular changes in our circadian rhythm, via jet lag or insomnia, can result in inflammation and problems in fat/sugar metabolism which in turn increase risk of cancer and heart disease.[30]

This may be due to the association of sleep and the gut microbiome. Disruptions to circadian rhythm can alter the ecosystem within the gut leading to effects on glucose metabolism and weight gain over the long term.[31] The gut microbiome is also affected by the quality of sleep in breathing conditions such as obstructive sleep apnea. In a mice model, disrupting breathing patterns for 6 weeks lead to a change in form and diversity of the gut microbiota.[32]

%20650x487px.jpg)

Beetroot Gaspacho: Image Courtesy of the Author

Mental Health

An emerging area of research is the association between the gut and mental health. The connection between the two is bi-directional, meaning a compromised gut can influence mental health and problems in mental wellness can also lead to changes in the gut microbiome so considering both together as a holistic approach is important.

According to the American Psychological Association (APA), 95% of the body’s feel-good hormone, serotonin, is produced by our gut bacteria, which potentially contributes to why encouraging the growth of good bacteria by consuming prebiotics could help treat depression and anxiety.[33] For instance, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) affects 10-15% of the UK population and is linked to having a leaky gut, but IBS is found at a higher rate of 25% in major depressive and general anxiety disorders.[34] When considering treatments, one study from the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry on 319 adolescents reported that established treatments for chronic depression and anxiety, such as SSRI antidepressants and CBT, initially improved symptoms in 48% of patients but only showed long-term effectiveness in 22% of patients.[35] On the other hand, a study on a magnesium chloride supplement showed a significant improvement in depression and anxiety in participants after just 2 weeks of treatment, even when controlling for age, gender and severity of condition.[36] This data is further strengthened by the fact that this improvement did not continue when the supplement was stopped. Magnesium use could be an influential treatment method in the future, especially considering it was at least 10 pence a day cheaper than traditionally prescribed drugs.[37]

Prebiotics, defined as non-digestible food ingredients that promote the growth of beneficial gut bacteria[38] could similarly be used to treat depression and anxiety.[33] Foods like garlic, onion and asparagus all help resist gastric acidity and stimulate the activity of bacteria associated with positive health benefits.[39] The fibre from these foods may even protect against cardio-vascular disease, obesity and type 2 diabetes, amongst other conditions.[40]

Positive nutritional input is therefore incredibly important, including the ability to help clear out waste products from metabolic processes in the brain. A diet deficient in essential micronutrients means that the brain cannot function as normal. The online programme www.resetyourguthealth.com which is tailored to your specific health conditions and eating preferences aims to provide all of these key nutrients via healthy and tasty recipes with food available from either main supermarkets or farmers markets. The feedback from customers has been overwhelmingly supportive of these ideas. For instance, Rebecca, a client complaining of brain fog and lack of energy, felt her energy levels were elevated 110% by the end of the 4-week programme.

Top Tip: Stress

The Bi-Directional Relationship between the Gut and Stress

Stress appears to be another constant presence in modern life but its negative relationship with our mental health, and physical health has repeatedly been shown in a multitude of studies. Whilst short term stress may be useful, chronic stress with its high levels of cortisol is associated with increased blood pressure and increased risk of heart attacks[41] and obesity-associated type 2 diabetes and cardio-vascular disease due to increased likelihood of the gain of fat in the abdominal area.[42] Stress has also been linked to acne onset and severity[43,44] as well as faster progression of cancer in mice models.[45] It has also been found to suppress the immune system[46] and the body’s ability to regulate inflammatory responses.[47] When your brain registers stress it releases a peptide called corticotropin releasing factors (CRP) which can result in gut inflammation. If this is chronic it has been linked to the development of anxiety and depression.[7]

Conclusion

This burgeoning area of health research has revealed the extent to which the microbiome can affect both your emotional and physical well-being. You can look after your gut by avoiding stress (as much as possible), getting a good amount of sleep every night and most of all providing your body with the nutrients it needs, and in turn your gut microbiome will look after you.

Health professionals from GPs to physiotherapist and individuals are using the www.resteyourguthealth.com programme as an effective tool to educate themselves and their patients how to maintain good gut health.

References

- Quigley EMM. Gut Bacteria in Health and Disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 9(9):560-569. 2013.

- O’Mahony C, Scully P, O’Mahony D, et al. Commensal-induced regulatory T cells mediate protection against pathogen-stimulated NF-κB activation. PLoS Pathog. 4(8). 2008.

- MD DP. New discoveries about brain and gut. In: Food Revolution Summit 2018.

- MD DK. True Health Initiative.

- Vighi G, Marcucci F, Sensi L, Di Cara G, Frati F. Allergy and the gastrointestinal system. Clin Exp Immunol.153 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):3-6. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03713.x. 2008.

- Abrahamsson TR, Jakobsson HE, Andersson AF, Björkstén B, Engstrand L, Jenmalm MC. Low gut microbiota diversity in early infancy precedes asthma at school age. Clin Exp Allergy. 44(6):842-850. doi:10.1111/cea.12253. 2014.

- Hart A, Kamm MA. Review article: Mechanisms of initiation and perpetuation of gut inflammation by stress. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 16(12):2017-2028. doi:10.1046/j. 2002.

- Turnbaugh PJ, Gordon JI. The core gut microbiome, energy balance and obesity. J Physiol. 2009;587(17):4153-4158. doi:10.1113/jphysiol. 174136. 2009.

- Ley R, Turnbaugh P, Klein S, Gordon J. Microbial ecology: human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature. 444(7122):10221023. doi:10.1038/nature4441021a. 2006.

- 10. Kuhnle GG, Tasevska N, Lentjes MA, et al. Association between sucrose intake and risk of overweight and obesity in a prospective sub-cohort of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer in Norfolk (EPIC-Norfolk). Public Health Nutr. 18(15):2815-2824. 2015.

- 11. Walker-Samuel S, Ramasawmy R, Torrealdea F, et al. In vivo imaging of glucose uptake and metabolism in tumors. Nat Med. 19(8):1067-1072. 2013.

- 12. Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, Obesity, and Mortality from Cancer in a Prospectively Studied Cohort of U.S. Adults. N Engl J Med. 348(17):1625-1638. 2003.

- 13. Bostick RM, Potter JD, Kushi LH, et al. Sugar, meat, and fat intake, and non-dietary risk factors for colon cancer incidence in Iowa women (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 5(1):38-52. 1994.

- 14. O’Keefe SJD, Li J V., Lahti L, et al. Fat, fibre and cancer risk in African Americans and rural Africans. Nat Commun. 6. 2015.

- 15. Spector T. My dad asked me to eat McDonald’s for 10 days. This is what happened. The Telegraph. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/foodanddrink/11603430/My-dad-made- me-eat-McDonalds-for-10-days.-This-is-what-happened.html. Published 2015.

- 16. Dentistry.co.uk. More than 160 operations every day to extract children’s teeth. http://www.dentistry.co.uk/2017/01/11/160 - extractions-childrens-teeth/

- 17. Ma J, Fox CS, Jacques PF, et al. Sugar-sweetened beverage, diet soda, and fatty liver disease in the Framingham Heart Study cohorts. J Hepatol. 63(2):462-469. 2015.

- 18. Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Despres JP, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar- sweetened beverages and risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 33(11):2477-2481. 2010.

- 19. Mueller NT, Odegaard A, Anderson K, et al. Soft drink and juice consumption and risk of pancreatic cancer: The singapore chinese health study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 19(2):447- 455. 2010.

- 20. Conlon M, Bird A. The Impact of Diet and Lifestyle on Gut Microbiota and Human Health. Nutrients. 2014;7(12):17-44

- 21. Kim MS, Hwang SS, Park EJ, Bae JW. Strict vegetarian diet improves the risk factors associated with metabolic diseases by modulating gut microbiota and reducing intestinal inflammation. Environ Microbiol Rep. 5(5):765-775. 2013.

- 22. Hemilä H. Vitamin C and infections. Nutrients.9(4). 2017.

- 23. Pearson DA. Bone health and osteoporosis: The role of vitamin K and potential antagonism by anticoagulants. Nutr Clin Pract. 22(5):517-544. 2007.

- 24. Tortorella SM, Royce SG, Licciardi P V., Karagiannis TC. Dietary Sulforaphane in Cancer Chemoprevention: The Role of Epigenetic Regulation and HDAC Inhibition. Antioxid Redox Signal. 22(16):1382-1424. 2015.

- 25. Frydoonfar HR, McGrath DR, Spigelman a D. Sulforaphane inhibits growth of a colon cancer cell line. Colorectal Dis. 6(1):28-31. 2004. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14692949

- 26. University of Oxford. Waking up to the health benefits of sleep. 30. 2016. https://www.rsph.org.uk/en/policy-and-projects/areas-of- work/waking-up-to-the-health-benefits-of-sleep.cfm

- 27. Health H. Repaying your sleep debt. Harvard Med Sch. 2018.

- 28. https://www.ndcn.ox.ac.uk/files/news/sleep-report-rsph.pdf

- 29. Morris A, Coverson D, Fike L, et al. Sleep Quality and Duration are Associated with Higher Levels of Inflammatory Biomarkers: the META-Health Study. Circulation. 122(Suppl 21):A17806 LP-A17806. 2010.

- 30. Gu F, Han J, Laden F, et al. Total and cause-specific mortality of US nurses working rotating night shifts. Am J Prev Med. 48(3):241-252. 2015.

- 31. Voigt RM, Forsyth CB, Green SJ, et al. Circadian disorganization alters intestinal microbiota. Cermakian N, ed. PLoS One. 9(5):e97500. 2014.

- 32. Moreno-Indias I, Torres M, Montserrat JM, et al. Intermittent hypoxia alters gut microbiota diversity in a mouse model of sleep apnoea. Eur Respir J. 45(4):1055-1065. 2015.

- 33. Schmidt K, Cowen PJ, Harmer CJ, Tzortzis G, Errington S, Burnet PWJ. Prebiotic intake reduces the waking cortisol response and alters emotional bias in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 232(10):1793-1801. doi:10.1007/s00213-014-3810-0. 2015.

- 34. Tsang SW, W. Auyeung KK, Bian ZX, Ko JKS. Pathogenesis, Experimental Models and Contemporary Pharmacotherapy of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Story About the Brain-Gut Axis. Curr Neuropharmacol. 14(8):842-856. doi:10.2174/1570159X14666160324144154. 2016.

- 35. Psychiatry. AA of C. No Title. 57;417. 2018.

- 36. Tarleton EK, Littenberg B, MacLean CD, Kennedy AG, Daley C. Role of magnesium supplementation in the treatment of depression: A randomized clinical trial. PLoS One. 12(6). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0180067. 2017.

- 37. Larner College of Medecine at the University of Vermont. With health care cuts looming, low cost magnesium a welcome option for treating. Sci Dly. 2017.

- 38. Gibson G, Roberfroid M. Dietary modulation of the human colonic microbiota - introducing the concept of prebiotics. J Nutr. 125(6):1401-1412. 1995.

- 39. https://www. cambridge. org/core/services/aop-cambridge- core/content/view/866DD38D124152BF0B54B5F5DE884BDE/S002 2046911002533a. pdf/counting ....

- 40. Brownawell A, Caers W, Gibson, G, et al. Prebiotics and the health benefits of fiber: current regulatory status, future research, and goals. 142(5):962-974 https://academic.oup.com/jn/article/142/5/962/4630853. 2012.

- 41. Guyton KZ, Loomis D, Grosse Y, et al. Carcinogenicity of tetrachlorvinphos, parathion, malathion, diazinon, and glyphosate. Lancet Oncol. 16(5):490-491. 2015.

- 42. Hecht SS, Carmella SG, Murphy SE. Effects of watercress consumption on urinary metabolites of nicotine in smokers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 8(10):907-913. 1999.

- 43. J.G. A, R.P. L, K.M. R, J.K. S. Nonpharmacological Strategies for Patients With Early-Stage Dementia or Mild Cognitive Impairment: A 10-Year Update. Res Gerontol Nurs. 10(1):5-11. 2017.

- 44. Zhang H, Wang Y, Jiang Z-M, et al. Impact of nutrition support on clinical outcome and cost-effectiveness analysis in patients at nutritional risk: A prospective cohort study with propensity score matching. Nutrition. 37:53-59. 2017.

- 45. Centers for Disease Control NC for CDP and HP. Physical activity and good nutrition: essential elements to prevent chronic diseases and obesity 2003.

- 46. Su X, Tamimi RM, Collins LC, et al. Intake of fiber and nuts during adolescence and incidence of proliferative benign breast disease. Cancer Causes Control. 21(7):1033-1046. 2010.

- 47. Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Doyle WJ, et al. Chronic stress, glucocorticoid receptor resistance, inflammation, and disease risk. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 109(16):5995-5999. 2012.

Comments:

-

No Article Comments available