Positive Health Online

Your Country

Remove bookmark

The Historical Background of Insulin

listed in diabetes, originally published in issue 179 - February 2011

For Type 1 diabetics, and a growing proportion of Type 2, the invention of insulin has literally been a lifesaver. Despite its every day usage, not many people know exactly what it is, and how it was founded. By taking a look back into the historical background of insulin, perhaps it will show diabetics a glimpse of what to expect in the future.

The 'Wasting Disease'

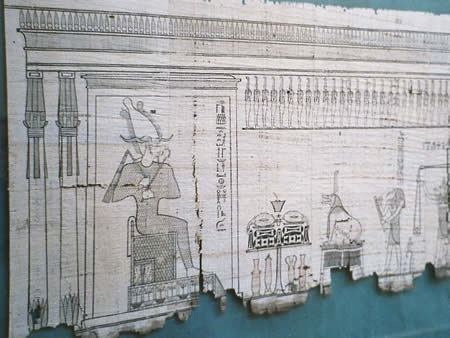

The first recorded account of diabetes was dated in 1550 BC. An Egyptian papyrus details a disease that causes the patient to lose weight quickly and frequently urinate. Greek Physician Aretaeus of Cappadocia named the condition diabetes in 150 A.D, meaning 'a flowing through'.

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Egypt.Papyrus.01.jpg

Photo taken by Hajor, Dec.2002. Released under cc.by.sa and/or GFDL.

He wrote, "Diabetes is a remarkable disorder, and one not very common to man. It consists of a moist and cold wasting of the flesh and limbs into urine, from a cause similar to that of dropsy; the secretion passes in the usual way, by the kidneys and the bladder. The patients never cease making water, but the discharge is as incessant as a sluice let off. This disease is chronic in character, and is slowly engendered, though the patient does not survive long when it is completely established for the marasmus (protein malnutrition) produced is rapid and death is speedy."

Frequent trips to the toilet were a classic symptom of diabetes three thousand years ago; the same logic still applies to present day. This is because the body is trying to flush out excess levels of glucose out of the body through urination. This is perhaps why ancient medics connected diabetes with other bodily organs.

Galen of Pergamum mistakenly diagnosed diabetes as a sickness of the kidneys in 164 AD. Physicians like Galen and Aretaeus understood the symptoms of the disease, but were dumbfounded on how to affectively treat patients.

However, this didn't stop medics from trying, and there have been many weird and wonderful treatments for diabetics prior to the discovery of insulin. In Ancient Greek times, oil of roses, dates, raw quinces and gruel were thought to ease patient suffering. Nonetheless, there is some sense in these suggestions. Quinces, for example, are rich in fibre. Fibre has been proven to help lower blood sugar levels as it slows down the absorption of sugar. More farfetched ideas in the 17th century consisted of broken red coral, sweet almonds, viper flesh jelly and nettles.

Urine has remained a consistently key element in understanding diabetes throughout the ages. By the 11th century it was primarily the job of 'water tasters' to diagnose diabetes. These medics would taste patient urine to test for sweetness. The term mellitus, which translates to 'honey' in Latin, was added to the diagnosis as a direct result of this procedure. To be diagnosed as diabetic during this time was considered to be a death sentence. It was commonly known as the 'wasting disease', as patients would literally waste away and die. Most sufferers would expect to die within a year of diagnosis.

For the next few hundred years doctors still continued using urine as a way of testing for the disease. In 1675 London physician Dr Thomas Willis used an 'ant test' in determining a patient's diagnosis. Dr Willis was behind the theory to collect samples of urine to leave out overnight, and see if ants were drawn near the sweetness of glucose by morning.

Dr Elliot P Joslin

Elliot Proctor Joslin was an American doctor born in 1869, considered to be a pioneer in understanding diabetes. Dr Joslin, often referred to as 'EJP', was the first doctor in America to specialize in the condition, creating the medical field of diabetes epidemiology. The Yale University and Harvard Medical School graduate had a personal connection to diabetes, as his mother and Aunt endured the disease in their later years. During his third year at medical school, EJP undertook the enormous task of compiling the world's first diabetes register. He did this by listing facts, progress and outcomes of patients and compared his findings with public data. Dr Joslin saw his first patient in 1898, where his clinic became the world's first diabetes care facility. EPJ's treatments consisted of early diagnosis, carbohydrate-restricted diets and fasting, alongside regular exercise and continuous testing. His earliest book, The Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus showed how his theories reduced the death rate of 1000 patients by 20 per cent. His second book, Diabetic Manual - For the Doctor and the Patient, published two years later, was the first attempt to educate patients about the nature of diabetes and how it can be controlled. This book gave diabetics across the world hope that diabetes could be incorporated into a healthy and happy lifestyle. It sent out a completely different message to Aretaeus' 'life with diabetes is short, disgusting painful.'

The Discovery of Insulin

The big breakthrough didn't come until 1921. Canadians Sir Frederick Banting and Dr Charles Best came up with the hypothesis that natural insulin was secreted from the pancreas. Banting was the first in nearly 3000 years to understand how the disease worked. The pair carried out research and experiments on diabetic dogs throughout the summer at the University of Toronto. Banting and Best discovered that the natural extract of pancreas secretion restored healthy metabolic functions to those suffering from diabetes. By January 1922, the researchers had perfected the extract enough to test it on humans. Fourteen year-old Leonard Thompson has been diabetic for 3 years, and on the brink of death. Weighing only 65lbs, the young boy was given Banting's and Best's new discovery. The results were revolutionary. Leonard's symptoms began to disappear and his strength was restored. This lifesaving extract was named insulin. Word quickly spread about this miracle treatment and the University of Toronto struggled to keep up with demands. An American company, Eli Lilly agreed to manufacture the extract in large quantities. In the UK, the Medical Research Council worked hard to distribute the drug that went on to save countless lives of adults and children. The duo made the insulin hormone patent available to producers for free, and made no attempt to profit from their breakthrough. It is for this selfless initiative that World Diabetes Day, held on November 14, is in honour of Banting's birthday.

The work of Banting and Best catapulted fundamental changes in how medics treated diabetes. It fuelled further developments and in 1935 Roger Hinsworth discovered that they were in fact two types of diabetes. Differentiating between Type 1 (insulin sensitive) and Type 2 (insulin insensitive) and allowed healthcare professionals to expand treatment options.

One year later, and scientists successfully found a way to slow down the pace at which insulin is released into the blood. By adding ingredients which break down in the body slowly, such as fish sperm protamine, one injection could last up to 36 hours. By the 1970s researchers produced small dosing insulin which mimicked the way normal functioning pancreases released insulin into the body at meal times.

From Pigs to Humans

Just thirty years ago scientists developed, American company Eli Lilly developed human insulin. Up until the 1980s insulin was still extracted from the pancreas of pigs and cattle. The reason for this being that the chemical structure of these animals is only slightly different from our own insulin. Using human insulin abolished any fears that potential diseases from animal insulin could be caught. It also meant that insulin could be mass produced and distributed around the globe in large quantities to pharmacies.Human insulin developed further in the 1990s and diabetics were introduced to analogue insulin. This new chemical substance allowed insulin to disperse quickly into the blood, meaning that the insulin could start working a few minutes after the injection. Another form of insulin analogue, Glargine, steadily releases insulin over a 24 hour period. These new and improved types of insulin have allowed diabetics to have full flexibility and control of their diabetes, according to their lifestyle.

The Future

We've come a long way from the original treatments of 'gruel and oils of roses' recommended over 3,000 years ago. Without men like EP Joslin, Banting and Best, it is hard to determine how many more millions of lives would have been lost to diabetes. Type 1 and 2 sufferers have a great deal to thank them for. It seems only right that World Diabetes Day is held in the honour of Banting's birthday. Scientists and researchers are looking for new ways in which to distribute insulin into the blood system. The insulin pump is becoming an increasingly attractive method of injecting in the UK, and is already commonly used in America. Although it was invented in the late 70s, the insulin pump has 'modernized' a great deal over the last 40 years; it has decreased in size from a backpack to something much more manageable. Around the size of a pager, the insulin pump mimics the body's normal release of insulin. A discrete, flexible tube is inserted just underneath the surface of a diabetic's skin, delivering a small measured dose of quick-acting insulin several times throughout the day. This eliminates the need for long-acting insulin, and dosage adjustments can be easily made prior to eating. Manufacturers are currently exploring the possibility of an implantable insulin pump, which would be controlled externally through a remote control.

Alternative methods of taking insulin are undergoing extensive research. Pills, inhalers, patches and aerosols could all be future possibilities. The challenge with edible insulin centres on the stomach's high levels of acid, which would destroy any insulin before it could reach the blood. Tests are being carried out to coat insulin extremely thin plastic to protect the drug from this problem.

Similarly, it is difficult to discover ways of distributing insulin without it actually passing through the skin. Ultrasound is a possibility, as the low frequency waves could alter the skin's permeability and allow insulin to sink through. Buccal (cheek) insulin, is also being considered as a viable way to distribute insulin. Through an aerosol device, diabetics would spray the insulin into the inner cheek where it can be absorbed through the inner cheek wall.

Dr Victoria King, Head of Research at leading health charity Diabetes UK, said: "Different administration of insulin could make a big difference to the lives of people with diabetes, and a great research effort is underway into different ways of administering insulin including orally, closed-loop insulin delivery, often called the artificial pancreas and through surgically implantable insulin resins.

"There has been much recent success in the development of an 'artificial pancreas' that combines a real-time sensor that measures glucose levels with a pump that delivers insulin automatically in response and such technology could vastly improve the quality of life for people with Type 1 diabetes and reduce the risk of the associated complications.

"In addition, as of 2009 we knew of at least seven different oral insulins in clinical development, and at least six others in the laboratory stage of development. How long both of these methods of insulin delivery might take to reach patients cannot be accurately estimated due to the complexities of research development, and because these delivery methods will need to be proven to work as well as and hopefully better than current methods of insulin delivery. But we are optimistic that that we will see some more positive developments soon."

The next big breakthrough in diabetes may be just around the corner, but it is safe to say that life for diabetics can only get better.

Comments:

-

No Article Comments available