Positive Health Online

Your Country

R-E-S-P-E-C-T - Strategies for Defusing Anger

by Dr Joseph Shrand(more info)

listed in holistic psychotherapy, originally published in issue 211 - January 2014

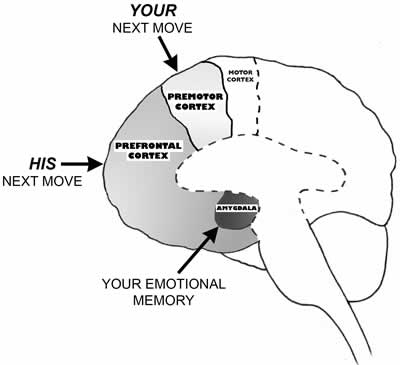

Place the palm of your hand on your forehead. Right behind this thin layer of skin and skull is your pre-frontal cortex or PFC, the executive centre of your brain. It is here that you analyze a problem, come up with a solution, execute a plan, and anticipate the consequence of that plan. Our PFC distinguishes us as human beings and gives us remarkable cognitive abilities. Ok, you can put your hand down and keep reading.

The pre-frontal cortex or PFC is the executive centre of your brain

Illustration by Sophia T Shrand

Deeper inside your brain resides the limbic system. This more ancient portion of the brain, the product of millions of years of evolution, directs our impulses and emotions, and houses our memories. Anger, when it flares instantaneously, derives from our limbic system, and leads to impulsive actions we usually regret. How many times have you done something based on raw emotion only to slap our foreheads as if trying to jump start the PFC and say, “What was I thinking!?” We weren’t. We had gone into what I call “limbic.”

Each of us has the capability of outsmarting those limbic impulses using our prefrontal cortex, the PFC, right behind your forehead. How many times has anger influenced our behaviour, perhaps even today in some small way? Have you ever shouted or sworn at someone who blocked you getting into the commuter train, resulting in your being late for work. Perhaps someone pushed you by mistake, nudging your arm, and causing you to spill your hot tea. Did you lash out and call them an idiot, even under your breath? Perhaps your boss gave you an impossible assignment, your partner forgot to pick up the milk from the grocery, or your child argued with you about going out with some friends when you wouldn’t let them. Maybe you have felt so insulted and disrespected that you went totally “limbic,” flying into a rage. The behaviour seemed to match the feeling at the time, but after the rush of limbic anger subsided, your reaction actually seemed irrational and immature and you felt regret. You may even have placed the palm of your hand on your forehead, shook your head, and wished you had thought things through and done something different.

But it’s not just our own anger that gets in the way of success; it’s often someone else’s angry feelings and outbursts that interfere with our success. In each of the above scenarios, imagine you were the one on the other side: the person who blocked you or the person who innocently nudged your arm and had to tolerate your verbal abuses, the uptight boss who couldn’t trust anyone, the partner who was exhausted from work, and knew that coming home without the milk was going to result in a tirade of shouting, the child whose angry parent wouldn’t allow him to see friends. When we know what makes us angry, we can decipher what makes other tick as well. We do this by following these basic behavioural premises:

Cover design by most of the Shrand Family; the cover model is

Becca Shrand, Dr. Shrand's youngest child.

- Recognize Rage. As soon as you recognize feelings of frustration, irritation, or aggression - all on a spectrum of anger, you’re shifting your brain from the limbic system to your prefrontal cortex. (If you want to, place the palm of your hand back on your forehead for a moment!) When you recognize anger emotions, you can begin to think, “Okay, I know anger is an emotion designed to change the behaviour of somebody else. What do I want to see different?” Ways to do this include writing an anger scale, all the words you would use for anger, and all the different levels of anger;

- Envision Envy. We human beings are basically animals that need the same things - food, shelter, and the ability to mate and reproduce. Another way to look at these needs is through the lens of the three Rs: Resources, Residence, and Relationships. Envy is when I think somebody is at an advantage over me in any one of those three domains. Most humans are exposed to the perception of other’s advantages all the time, so it’s important to envision envy in yourself. This way you can perceive it in others and diffuse the negative and unenviable emotion that envy brings about. Being angry at your boss because he has more power and is putting you in an impossible situation is an example of envy, as is the angry child envious of the power their parent has to restrict them from going out.

- Sense suspicion. I sense suspicion when I think somebody may threaten or take my resources, residence, and relationships. Since we modern humans all benefit of having basically the same evolved brain, if I’m sensing this, everyone else is too. So it becomes much easier to know when others sense suspicion, and when they do we can outsmart and modulate another person’s suspicion and anger response. The person who cut you off or nudged your arm has taken a resource of your place in line or a sip of tea. You may become angry as your suspicion grows they will try to take more. Not bringing home the milk may activate anger in you worrying your partner sees you as inadequate. And how often have parents become angry with their kids, suspicious of their child’s motivation and insistence in going out with some friends?

- Project peace. When I project peace, I’m actually sending a message into another person’s brain, activating parts called mirror neurons. These are brain cells that mirror what other people do. If I perceive that you are afraid, I may begin to feel afraid as well no matter why you’re afraid. And if I see that you are angry, I might mirror anger as well. But by projecting peace, you’re sending a message very quickly to another person: “Listen, relax, chill,” or what have you in the ‘calmosphere’;

- Engage empathy. Empathy is our ability to appreciate what other people think or feel. By engaging empathy, you are sending a message to another person that you are interested in them, that you respect where they are coming from. In our heart of hearts, a human being simply wants to be respected and valued by another human being. If you’re valuable, you’re part of a group. You’re not going to be kicked out. Value leads to trust, and trust creates an important chemical in the brain called oxytocin. And if you’re valuable, you can stay in the group, you can trust people, and you’re going to be safe;

- Communicate clearly. By communicating clearly, we’re sending a message. I recognize you’re angry, are you envious of me or suspicious? I’m peaceful, I’m projecting peace. I’m interested, I’m engaging empathy. You’re telling someone you respect them and that they’re valuable. Respect leads to value, value leads to trust. When we communicate these behaviours clearly, we and others keep feelings of anger at bay;

- Trade thanks. Ninety percent of the time in our culture, when someone says thank you, what do you say? You’re welcome. These are not insignificant words. Gratitude is the most amazing thing, because when we do acknowledge another person’s help to us, we’re actually activating altruism. When I thank you, I’m acknowledging you as a benefactor. You’re acknowledging me as a recipient. Our verbal exchange recognizes each other’s value to each other. While one might be wealthier or more powerful in some ways, in this exchange we are equals in respect of the other. Thanking someone for what they have done also sends a message that they can rely on you in the future, making them feel good about having shared a valuable resource, residence, or relationship.

If you look at the first letters of all these steps they spell R-E-S-P-E-C-T. Respect is at the heart of all these simple and complex human arrangements that happen every second of every day. Think about it - when is the last time you got angry at someone you really believed was treating you with respect? You don’t. The brain is not designed to respond in anger when it feels respected. It can’t, and I believe this has the same reliability as gravity. Apples don’t fall up and the brain does not activate anger when it feels respected. Being respected feels great, and by practising respect in every exchange, we all get less angry.

You can start using this technique today. If a person cuts you off trying to get into the train, rather than get angry, what would happen if you said, “Sorry. Didn’t know I was in your way?” If someone nudges your arm, rather than get angry say, “Accidents happen. No worries”. If your boss given you an impossible task, ask for help with a phrase like, “How can I get this done the best way for you?” If you forget to bring home the milk offer to help in some other way, or, if you can afford it, go out for a meal instead. In all of these you let the other person know that they are valuable, if they are someone you work with, someone you live with, or even a complete stranger.

If your child is rude, rather than get angry model the calm and respect you want them to give you, then stop, look, and listen to what they have to say. This one is particularly important as we lead such busy lives our children may sometimes feel overlooked. When you stop what you are doing, look at them, and then listen you send them the message that they are important and valuable to you. By giving the gift of time you can begin to learn more about who they are and why it is so important for them to go out with that friend that afternoon. (And one last little detail: I suggest we talk with a person, not to them. Talking to someone feels like talking at them, unidirectional. But talking with someone creates a dialogue, and a relationship with enormous potential.)

In each of these ways we remind another person of their value by treating them with respect, and defusing their anger. Once you have two brains living in the PFC you can get so much more accomplished than with two limbic brains feeding, fuelling, and igniting each other’s anger bomb. Keep it frontal, don’t go limbic!

So, place your hand back on your forehead. This spot right here provides us all with the key to outsmarting anger: using our PFC to anticipate the consequences of our actions, and recognize that someone else’s anger can be modulated by treating them with respect. For more information and helpful exercises, read my book, Outsmarting Anger: Seven Strategies to Defuse our Most Dangerous Emotion. Keep it frontal, don’t go limbic. (You can take your hand off your forehead now!)

Further Information

Dr Shrand's books Outsmarting Anger: Seven Strategies to Defuse our most Dangerous Emotion and Manage your Stress: Overcoming Stress in the Modern World are available in bookstores, www.amazon.com and other online venues. Both books are available in Kindle. Outsmarting Anger also available as an audiobook narrated by Dr. Shrand, Leigh Devine, and two of Dr. Shrand's children: aspiring actress Sophia Shrand, and aspiring college student, Galen Shrand, is available on Amazon:

www.amazon.co.uk/Outsmarting-Anger-Strategies-Defusing-Dangerous/dp/1118135482

www.amazon.com/Outsmarting-Anger-Strategies-Defusing-Dangerous/dp/1118135482

Comments:

-

No Article Comments available