Positive Health Online

Your Country

How Meditation Transformed My Life

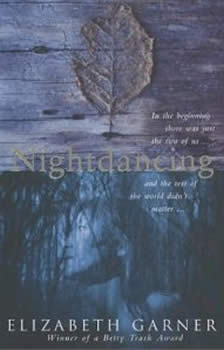

by Elizabeth Garner(more info)

listed in meditation, originally published in issue 152 - November 2008

In 2001 I was 26 years-old and had everything I thought I wanted. I was working in London as a feature film script editor. I had an office in the heart of Soho, and I loved the hustle and bustle of this vibrant part of the city. Long days were rewarded by drinks at a club or a screening of the latest movie. But I wasn't just in it for the social life. I thrived on the challenge of teaming up directors with screenwriters and creating stories. Over a couple of years I developed a range of film scripts, one of which was in the process of being optioned by a major film studio. In what spare time I had, I was also following my own private ambition: to write a novel. Lots of hard graft and a very supportive agent resulted in a publishing deal at the end of the year. I was delighted, and looking forward to the challenges of 2002.

Although I was certainly ambitious, I also really valued my life outside work. I had a great group of friends whom I'd met at college and who, like me, were finding their feet in the city. We supported each other through the angst of our early 20s: family problems, relationship trauma, work pressures – and we also knew how to party! That December we were having an early Christmas celebration at out local curry house. The food was excellent, the beer was flowing, we were all in good spirits and then, suddenly, I couldn't breathe. Then I started to hyper-ventilate. For a moment I thought it was a chilli-induced affliction. But then my vision blurred and everything went black. I came to, to find my friends calling an ambulance. Apparently I had fainted and gone into spasm. I was terrified.

That night I stayed awake, self-diagnosing: I must be epileptic, or have a brain tumour. Apparently not. My doctor told me it was a panic attack. He said that this was a classic sign of stress, and that I should take a good look at my lifestyle. I did: it seemed fine to me. Yes, I worked hard and played hard, but so did everyone I knew. I was happy, very happy in fact. It was inconceivable that my state of mind was responsible for such a horrendous experience. I dismissed the analysis: it was a one-off, a freak event and nothing to worry about.

But I was wrong. Over the next six months the attacks continued, with alarming frequency. I never fainted again, but I would find myself suddenly unable to breathe, and then my vision would go. They came on with virtually no warning, though it always seemed to happen when I was in a large group of people. And, inevitably, the fear of an attack became a problem in itself. I couldn't relax when I was out. I found that I had to always be able to see a clear line to the door when I was in a busy room. Clearly parties and clubbing weren't an option anymore, and as the months passed I became more of a hermit. Then one day I was too terrified to get on the tube. Then I could only cope with being on a bus if I could get a seat by a window. I managed to hold onto my job, but found myself spending a fortune on taxis.

Meditation at the Buddhist Centre

My friends were as supportive as ever, but my behaviour was scaring them. My confidence was shot to pieces: I was nervous all the time. And even though I had scaled-back my lifestyle, there was no improvement. I was getting panic attacks at home – the one place where I should have felt safe. By this point I was desperate to regain some kind of control over my life. My doctor had told me that I needed to make changes. I started with the most obvious choice. If my body was rebelling against me, then it might just calm down if I modified my diet. I went to my local health food shop to stock up, and there I saw a leaflet on meditation. The classes were being held at the London Buddhist Centre, just around the corner. The pamphlet told me meditation was a good antidote to the stress and strains of the modern world. I was sold.

When I first walked into the class, I was faced with my worst fear: a crowded room. Then we were all told to sit on cushions, and the door was shut. We were instructed to close our eyes and pay attention to our breathing. I did – and mine was frantic. The teacher talked about recognizing the thoughts and emotions that emerged during the course of the meditation: recognizing, but not judging them. I did, and found I was consumed with anxiety. I couldn't stop fixating on the tiniest details of my day. But the strangest thing was, I wasn't concerned about practical minutiae – the unreturned phone calls, the unposted documents. My mind was full of all the stories that I was working on. It was like watching several unfinished movies playing in my head, concurrently. With my subconscious full of people that didn't exist, no wonder I was having trouble with real-life crowds.

Unfortunately, understanding the problem didn't mean that I had solved it. The Buddhist centre taught two basic meditation practices: one intended to develop positive emotion, the other to help you become more calm, concentrated and self-aware: all the tools that a girl needs to stop panicking and start living again.

A Touch of Yoga

But it wasn't quite that simple. To my amazement, I found that every time I sat down to meditate an incredibly critical inner voice emerged. It kept on telling me I was wasting my time, I had so much to do, how could I possibly justify just sitting there? It told me that I looked ridiculous, and how could this hippy-nonsense possibly help? The forcefulness of this voice shocked me, but it also unlocked the first part of the puzzle: no wonder I was in such a state of panic if my subconscious was shouting at me all the time!

When I spoke to the meditation teacher about this he told me that this was actually quite a common experience: we are our own worst critics. He suggested it was time for me to give myself a break. Constant analysis wasn't productive. Just as the mind can affect the body, so can the body help to correct the mind. All great in theory, but what, practically, could I do about it? His solution was less thought, more action. He recommended a yoga class, led by a fellow Buddhist.

I expected a gentle, touchy-feely kind of workout. It was anything but. The teacher put us all through our paces and 1½ hours of improbable stretching later, I ached all over but I felt, for the first time in months, safe and comfortable. Also, the incidental commentary of the yoga teacher struck a real chord. "Listen to your body!" he said, again and again, "It will tell you what is acceptable!" I suddenly realized: I had been living entirely in my head. My only recreation from that had been nights down the pub. The panic attacks were my body crying out for me to take notice of it.

In Conclusion

Again, the understanding didn't provide a quick-fix solution. Often I found myself resenting the time that I spent with this new practice but I couldn't argue with the facts: the more time I spent on yoga and meditation, the less I panicked. After about a year I had incorporated it into my daily routine. About three months after making that adjustment, the attacks stopped altogether. I haven't had one for five years now.

Looking back on the experience, I don't believe that I found some kind of miracle cure to my condition. But I do think that meditation and yoga forced me to slow down a little, and gave me invaluable tools with which to look at my life and take stock; to work out what was good for me and what wasn't. I still live in my head – editing film scripts and writing novels. But I am conscious that nothing is to be gained by listening to that negative voice that still pops up occasionally. I actively work to change the fears of "what if I can't do this?" to "what if I can?"

I have also learnt to balance my fictional worlds with regular practice, and also basic physical activity that gives me pleasure and benefits others: namely gardening and cooking. I'm no saint and I certainly still enjoy a night socializing, but it is no longer my only way of relaxing. Although my panic attacks felt like small deaths, I now understand that they actually taught me how to live.

Further Information

For more information visit www.lbc.org.uk

Comments:

-

No Article Comments available