Positive Health Online

Your Country

Words that Can Heal in Turbulent Times

listed in nlp, originally published in issue 284 - February 2023

In times of plague, we seek healing, in times of war we seek peace,

in times of hunger we seek nourishment.

When our world is falling apart at every level, and human extinction

beckons from every direction, we look around for help.

What we find … is each other.

Our 24-hour cycle of rolling news reports thrives on disaster and conflict; whilst advertisers know our attention is compelled by negative emotions; fear, anger, envy and rage.

We know our media is controlled by billionaires and our politics is controlled by the banks and big corporations. How can we believe we have any real power to affect either events or how we feel about them?

Hang on a moment. What was it cheered you the last time you felt good in the course of an ordinary day?

I’m going to guess it was something someone said. Even just “How are you?”

A Few Words that Let You Know Someone Else was There

We can only hope to influence the big stuff by joining together to address our concerns. For example, by giving to charities, and/or by joining groups campaigning for environmental protections, economic justice, improvements in public health and the defence of human rights. These activities allow us to contribute our small part to bigger causes.

As individuals, we have unique power over the qualitative experience of our own days.

That begins with the power of our words, both the ones we say to ourselves and the ones we say to others.

We may imagine that critical words can get people to do what we want or stop doing what we don’t want. Reward and punishment surely works, does it not?

Modern psychology says no. Our deepest fear is being ignored. If good behaviour is ignored, and bad behaviour at least gets the attention of a punishment, we are in effect rewarding bad behaviour.

Which gets more media attention, a crime, or a good deed? Our politicians want to spend millions building prisons – an extremely expensive form of punishment. But they insist we can’t possibly afford to pay the people who keep society going – nurses, carers, bus/train drivers, postmen and dustmen – enough to keep their families warm and fed.

What can ‘just words’ achieve, in this environment? They can improve the quality of our days, and the days of those around us. They can enable us to increase the behaviour we want from others in ways that make them feel good about themselves.

And, very importantly, they can counter the self-critical words which might paralyse us in the face of problems that are not our fault. It is not ‘poor budgeting’ if you can’t make ends meet when prices have risen and your income hasn’t.

Your child has done the dishes but made rather a mess of it. Thank him or her for the effort. Point out everything that has been done well. Maybe offer help with how to do some of it better/more efficiently. If doing the dishes is an opportunity to win gratitude, affection and praise maybe your child will actually want to do it again.

If, like me, you are old, not very well, and in need of attention and help, you’ve probably noticed how easy it is to feel crotchety and neglected. Consequently, you notice the three things that haven’t been done rather than the ten things that have. But if we want our family and our friends to want to see us, it makes sense to ensure that the visit is a rewarding experience for them. Thank them for coming (do not complain that it’s not often enough). Thank them for what they do. Let them know you are aware of what trouble and hardships are involved for them. Be interested in their health, not just your own.

In any conversation there will be opportunities to point out the everyday successes and achievements which most of us don’t stop to celebrate amongst the general grind of getting though each day. Be the person who does notice those achievements, both your own and those of your friends.

Even big industry has recognized the importance of positive affirmation. Those signs on the backs of lorries, inviting us to let the company know about examples of good driving! The driver must feel a little better than carrying an invitation to report bad driving, though probably the intention is the same…

Here are some further examples:

Teaching Ourselves How To Find A Perspective

What words can we use to help ourselves when we are in difficult situations? For example, when we are worried about something we’ve done, or when we conflict with someone, we are in situations we need to change but can’t figure out how.

It is quite likely that we are saying very self-critical things to ourselves, thinking of solutions that we already know won’t work, or already know we won’t be able to carry out, and blaming ourselves.

How can we get a different perspective?

From the past: When have we been in a similar situation? Were we able to solve it then? What did we do that time? What worked the best for us?

From the future: In five years when we are looking back on the current situation, what will we see? Will we see a future in which the problem has been resolved, or become unimportant, or that life has taken a different direction? What advice would our future self-have for us?

Giving ourselves a different time perspective enables us to realise we have already dealt successfully with similar situations. Or that we don’t need to attribute so much importance to this issue. Or that the outcome could lead to a completely unpredicted future.

From a Different Position

Can we imagine being an interested and sympathetic bystander to our situation? (Looking on from somewhere else in the room…)

Imagining that we are a friendly advisor allows us to let go of unhelpful self-criticism and give ourselves more constructive advice. What we would say to a friend in trouble tends to be much more helpful than the usually harsh things we say to ourselves.

Reviewing the situation from this perspective is a way to discover hidden strengths as the answers often lie within our own capabilities.

Words that can Help when We are in Conflict with Someone Else

‘Let’s start with what we can agree on!’

We both feel strongly about the situation.

We both want to ‘win’.

We both want to get what it is that we want.

(And just possibly, we both want to end up not being angry with each other.)

We’ve found some things we can agree on. That phrase sets a new agenda – instead of fighting each other, we can become allies in a common cause – to make a plan that could give each of us our desired outcomes. Both will be winners when we’ve worked this out.

Being in the Other’s Shoes

In a situation involving interpersonal conflict, could we imagine for a minute or so being that other person? Imagine saying their words: sitting, moving, gesturing, breathing in synchrony with them? This creates powerful empathy, insight and understanding based on how it feels to be them.

You could try out this strategy in agreement with the other person – suggest that you each swap places and try to imagine being the other. The more carefully you mimic each other, the greater your understanding will become of the feelings underlying the disagreement. This new level of insight can help you each to find a path to resolution.

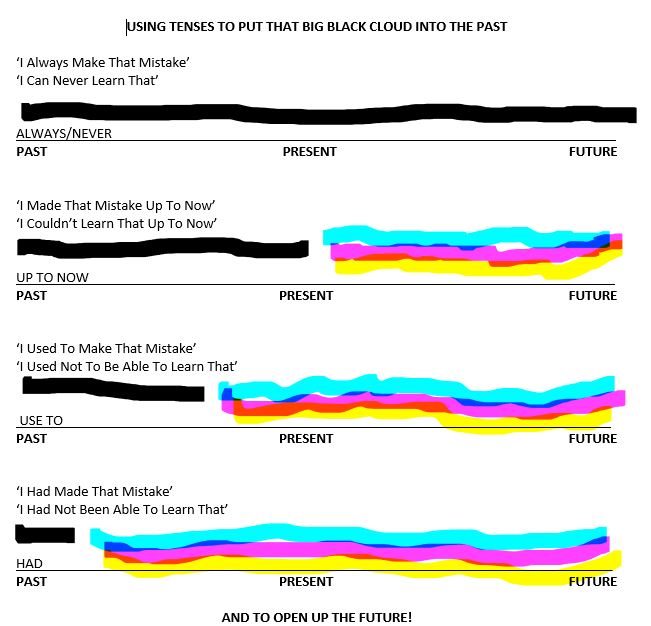

More On Timeline – Playing With Tenses

Imagine a timeline which runs from your past to your future.

Now consider these statements:

That always happens to me.

I always make that mistake.

I never succeed at that.

The words ‘always’ and ‘never’ put these situations across the whole timeline: the entire past, present and future.

Now try adding the phrase ‘up to now’.

It’s always happened to me up to now.

I’ve always made that mistake up to now.

I’ve never succeeded at that up to now.

This cuts these pessimistic generalisations off at the present and opens the future to other possibilities.

Now try pushing these statements a bit further into the past by replacing ‘always’ and ‘never’ with ‘used to’.

It used to happen to me.

I used to make that mistake.

I used be unsuccessful at that.

Then push it even further into the past by using ‘had’.

That had happened to me.

I had made that mistake.

I had been unsuccessful at that.

………………………………….

At a very deep level, these changes of tense free the mind to find new possibilities in the future; to take a more positive look at the past, to find the exceptions to these absolutes.

Brown cow from Pixabay; Purple Cow Tail Snip from Clipart Max

Brown Cow Author Credit: Lady Lioness

Finally: How to Get Rid of a Purple Cow (Why Not to Shout ‘Don’t Fall’!)

Make a mental picture of a purple cow.

Now try not to see the purple cow.

Spend a few seconds trying not to see the purple cow.

(I’m serious, keep trying for a bit longer.)

I’m going to guess that ‘trying not to’ didn’t work very well.

(Unless maybe you put a wall in front of it!)

Now I’m going to ask you to make a clear and vivid image of a brown cow.

Done?

What happened to the purple cow?

Our brain can’t deal well with a negative. In order to ‘not do’ something, it has to represent the something it is not to do. Trying to ‘not see’ the purple cow requires you first to see it.

On the other hand, focusing on making an image of the brown cow causes it simply to vanish.

As an exercise, this has no important consequences. In real life, It does.

If you’ve just noticed your child trying to walk along the top of the garden wall, your shouting ‘don’t Fall’ could have consequences – do you really want your child to hear a shouted ‘fall!’? ‘Be careful’, ‘Stay safe’, or even ‘You’re good at walking on walls!’ would be safer thoughts to put in their mind.

Given our mind’s capabilities for reacting positively to suggestions, what do you say to your friend who is telling you about something bad or even tragic that has happened to them?

It is instinctive to say, ‘oh that’s awful’, ‘how terrible’, ‘you must be devastated’. But do you really want to suggest how terrible they must be feeling? They are feeling terrible already, they don’t need you to reinforce it. ‘You must be devastated’ is, to our literal mind, a command. Do you really want to command them to feel devastated?

One alternative is to speak about your own feelings, not theirs. ‘I feel devastated for you.’ ‘I’m so sorry this has happened to you.’

Another is to speak about their strengths: ‘It’s going to take so much courage/strength for you to deal with this!’

Another is to take advantage of the mind’s inability to deal with a negative: ‘It would be almost impossible for you to imagine ever being happy again.’

You’ve told your friend that you feel devastated, that they will deal with this because of their courage/strength, and that, however unimaginable at the moment, it is possible a time will come when they will be able to feel happy again.

Isn’t that what you really wanted to say?

Final Words to My Readers

Take care, stay safe, be kind (it’s good for your immune system!)

Notes

Timeline, Perceptual Positions, Internal Dialogue, Language Patterns are taught in NLP Practitioner and Master Practitioner courses based on the work of Richard Bandler, John Grinder, Tad James, Robert Dilts.

The concept of resolving conflict by first identifying common ground arose in group-work theory and will be part of modern conflict-resolution training for negotiators in many situations.

Comments:

-

No Article Comments available