Positive Health Online

Your Country

Optimizing Breathing Chemistry: Foundation for Healing

listed in breathing, originally published in issue 122 - April 2006

Breathing is intrinsic to life, and our breathing 'behaviour' is at the heart and foundation of our body and mind's health. Breathing facilitates and governs internal chemistry, specifically the acid /base physiology. This second-by-second respiratory regulation repeated on average 20,000 times a day, either creates a balanced state of homeostasis or leads to deregulated chemistry causing many 'stress-related' symptoms.

It is the stress that we experience in our daily lives that can lead to this deregulating effect upon our physiology and psychology. This stress can emerge from demands in the workplace, dysfunctional relationships, lack of or too brutal physical exercise, a poor diet or feeling overwhelmed by the pace of our lifestyles.

An integral part of this stress response is an increase in our breathing rate and depth, which leads to an over-ventilation of the lungs. We become 'chest breathers', often using our mouths instead of the natural diaphragmatic nose breathing that we experienced when first born. In fact, the first mouth breath a baby takes using the chest muscles is often when he or she first cries – a distressed, uncomfortable response to a stressor. As time progresses, this stressed breathing pattern can become the norm.

Overbreathing – Hyperventilation

Professor Peter Litchfield, a leading figure in the studies of behavioural physiology, comments: "Overbreathing is undoubtedly one of the most insidious and dangerous behaviours/responses to environmental, task, emotional, cognitive, and relationship challenges in our daily lives. Overbreathing can be a dangerous behaviour immediately triggering and/or exacerbating a wide variety of serious physical and mental symptoms, complaints, and deficits in health and human performance."[1]

The following is a quotation from a book chapter written by Dr Herbert Fensterheim, a highly respected and internationally prominent author and psychotherapist, and it points to the fundamental importance of evaluating breathing chemistry.

"Given the high frequency of incorrect breathing patterns in the adult population, attention to the symptoms of hyperventilation [overbreathing] should be a routine part of every psychological evaluation, regardless of the specific presenting complaints. Faulty breathing patterns affect patients differently. They may be the central problem, directly bringing on the pathological symptoms; they may magnify, exacerbate, or maintain symptoms brought on by other causes; or they may be involved in peripheral problems that must be ameliorated before psychotherapeutic access is gained to the core treatment targets. Their manifestations may be direct and obvious, as when overbreathing leads to a panic attack, or they may initiate or maintain subtle symptoms that perpetuate an entire personality disorder. Diagnosis of hyperventilatory [overbreathing] conditions is crucial."[2]

Breathing Chemistry

Extensive scientific research over 30 years has linked hypocapnia, low CO2 levels in the body caused by overbreathing behaviour, with symptoms such as hypoxia caused by reduced blood flow and oxygenation to muscle tissue and organs, vasoconstriction leading to asthma, high blood pressure and muscle tension and over stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system leading to anxiety, insomnia, exhaustion and burnout.

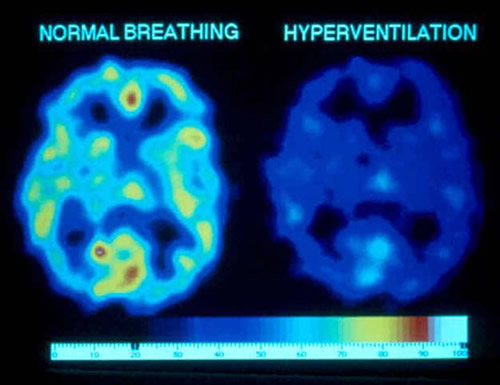

To understand the causative factors of the symptoms above, we need to examine the basic principles of respiratory chemistry. The fall of the carbon dioxide concentration in the body from overbreathing leads to an alkaline shift in the blood as less carbonic acid is produced. In this condition of respiratory alkalosis, the oxygen molecule clings more tightly to the haemoglobin in the red blood cells. This causes less oxygen to be delivered to the cells of the body. Add the vasoconstrictive effects of hypocapnia of smooth muscle in the blood vessels, then hypoxia can result. (See Diagram 1)

Diagram 1. Effects of overbreathing on Cerebral O2.1 Reduction of O2 Availability by 40 percent (Red = most O2, dark blue = least O2). In this image, oxygen availability in the brain is reduced by 40 percent as a result of about a minute of overbreathing (hyperventilation). Not only is oxygen availability reduced, but glucose critical to brain functioning is also markedly reduced as a result of cerebral vasoconstriction.

The body is in a continual synergetic flux with the aim of restoring and maintaining homeostasis which can be described as: "Various feedback loops maintain physiological processes within the narrow range that is compatible with life."[3]

The increased alkalinity of the blood triggers a compensatory effect known as renal compensation which filters off bicarbonates in the kidneys in an attempt to restore normal pH levels. For example: have you ever needed a visit to the loo when about to give a speech or enter a room for an interview? The challenging situation causes overbreathing leading to increased alkalinity of the blood and renal compensation leads to a need to urinate the bicarbonates out of the system.

Clinical Consequences of Dysfunctional Breathing Chemistry

A chronic hypocapnic condition severely depletes the bicarbonate buffering system that neutralizes the build up of lactic acid produced during physical exercise. This then can lead to increased overbreathing as a short term solution to increased acidity which quickly leads to the point of exhaustion.

In a self regulated, homeostatically balanced individual this means resilience, stamina and quick recovery as the buffer mechanism is maintaining homeostasis until natural tiredness signals rest. But a deregulated, maladapted chemistry of a stressed individual can lead to exhaustion whilst performing tasks as undemanding as walking or even communicating. In Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), the deregulated respiratory chemistry leading to debilitating exhaustion is often initiated by long term stress or trauma, creating a dysfunctional breathing disorder.

The sympathetic over-arousal state created by chronic overbreathing leads to an inability to self-regulate, or in simple terms, be able to relax and restore energy levels through calming activities and sound healthy sleep.

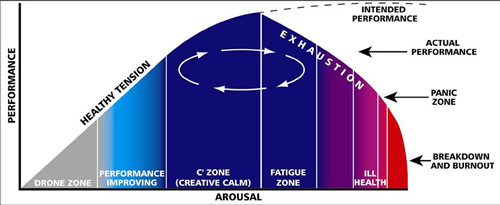

The human function curve (see Diagram 2) a modification of the Yerkes-Dodson law, was developed to explain the difference between healthy arousal and exhausted over-arousal. Healthy tension is represented by the up slope of the curve, where performance tends to improve in proportion to arousal. In this state of mind and body, activity can be balanced by calming relaxation activity, and so homeostasis is maintained. On the down slope, effort continues despite fatigue; arousal increases but performance deteriorates, and if the struggle continues, exhaustion worsens and eventually health breaks down.

Dysfunctional breathing often leads to a closed, locked-in personality and physicality that can respond poorly or slowly to restorative health approaches. The inextricable relationship between the fight/flight response and overbreathing is demonstrated when you perform a simple test. Using a capnotrainer, a device that measures the partial pressure of exhaled carbon dioxide, the subject is asked to take big deep breaths. The computer readout shows that as the breathing depth increases the end tidal CO2 levels drop. As the breathing chemistry is altered within a matter of seconds, a physiological and psychological shift occurs. Depending on the subject's predisposition, symptoms such as increased anxiety, tightness in the chest, cold clammy hands, increase in blood pressure and heart rate begin to emerge. A common experience is a feeling of light-headedness which can be explained by the hypoxia of the brain illustrated in Diagram 1.

There is a fine line between vigilance and stress. In the transition from vigilance to stress, i.e., from positive attentiveness to guarded defensiveness (fight-flight behavioural patterns), overbreathing may be immediately instated with its debilitating effects occurring within less than a minute.[1]

Corrective Breathing

Healthy breathing behaviour opens up the individual physiologically, stimulating vasodilatation, increased oxygenation, improved blood supply, and relaxed muscle tone, as well as psychologically by allowing parasympathetic access, letting go, and dropping of guarded, defensive behaviour. This 'openness', allows for embracement, hope, learning and progress which provides an optimal state for further healing work, be it counselling, coaching, body work or educational environments where improved cognitive access and embracing attitudes foster greater learning potential.

The clinical application of corrective breathing involves identifying dysfunctional patterns and behaviours by monitoring breathing chemistry with a breakthrough device using biofeedback as objective evidence. Using a Capnotrainer, a portable instrument that measures end-tidal carbon dioxide levels, the practitioner is able to display a client's breathing chemistry and the impact this might be having on their health. With breathing behaviour visually revealed and learning to 'feel' the respiratory changes having an effect on physiological and psychological states, breathing correction and optimization is possible.

Corrective breathing aims to redress the negative effects of our unconscious breathing habits by fusing newly available cutting edge Capnometry technology (only previously used in Accident and Emergency departments and ambulances) with the holistic practice of Buteyko, a Russian breathing approach that also aims to restore healthy carbon dioxide levels. Dysfunctional breathing can upset the body's chemistry and lead to symptoms such as asthma, sleep apnoea and insomnia, anxiety and allergic responses. Corrective breathing provides a self-managing framework to restore balance, resilience and optimal functioning of the body's natural healing ability.

Dr David Beales, a highly respected Educator of Mind/Body Medicine emphasizes the importance of a patient learning how to self regulate:

"Many symptoms have no obvious cause, to the frustration of both patient and health professional. But if consultation aims to establish why self-regulation is lost, the patient can actively participate in restoring their own health. Homeostatic self-regulation is central to diagnosis and treatment."[4]

Restoring internal mind/body balance and setting a foundation for long term healing and resilient health is the aim of corrective breathing. By focusing on optimizing breathing chemistry, not necessarily by focusing on the mechanics which can easily be misinterpreted, clear objectives are defined and measurable using biofeedback data. The patient is able to see how their breathing is affecting their health and follow the progress they are making in a live session. The connection is powerful. For many, it is the first time they realize that there is a possibility to consciously affect internal states of mind and body. This empowerment to self-govern is the first step towards establishing a healthy life in the widest possible sense. Learning to breathe from the inside out rather than from the outside in, gives a sense of confidence and security with the knowledge that regardless of the environmental stresses, inner balance and harmony can be maintained.

Breathing evaluation and training may be useful for restorative and training applications by health professionals and patients, performance trainers and athletes/artists, corporate trainers and trainees, behavioural health professionals and clients, human service providers and clients, educators and students, and researchers.

Examples of application include: improving memory, enhancing thinking and problem solving skills, attention training (e.g., attention deficit), improving concentration (playing an instrument), reducing anxiety (e.g., public speaking, test taking), managing anger, decreasing fatigue, managing stress, increasing alertness and readiness, reducing muscle tension, facilitating relaxation, diminishing physical pain, maximizing performance training, natural child birth preparation, and evaluating and improving physical condition.

References:

1. Peter M. Litchfield, Ph.D. California Biofeedback. Vol. 19, No. 1. Spring 2003.

2. Dr Herbert Fensterheim. Behavioral and Psychological Approaches to Breathing Disorders. Chapter 9. 1994.

3. Guyton AL and Hall JE. Textbook of Medical Physiology. 10th Edition. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 2001.

4. Dr David Beales. Journal of Holistic Healthcare. Vol 1, Issue 3, p15. 2004.

Comments:

-

No Article Comments available